Reading Group

This is a good week to read books that make you feel uncomfortable.

Actually, any week is, but given the latest news about efforts to censor books and keep unsettling ideas out of the hands of school-age kids, this seems to be a particularly appropriate moment in history to engage in what in more rational days would be called “learning.”

Tell that to the genius school board in Tennessee that is targeting Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Holocaust narrative, “Maus,” as subversive, pornographic and inappropriate for school libraries. Or to like-minded educational authorities in Texas whose purge of controversial textbook content has a chilling effect nationwide. That’s because publishers mindful of that lucrative market tend to target the lowest common denominator of tolerance about messy stories like the American genocide of indigenous peoples, the role of slavery in the making of our economy or the enduring legacy of Jim Crow and racism.

In many states today, initiatives by educational administrators and legislative bodies are targeting the teaching of historical material that makes some students (read ”white students”) squirm. It’s the next logical step in the authoritarian censorship of ideas that have an edge. Having banned the teaching of a subject, Critical Race Theory, that is not actually taught in public elementary and high schools, the self-appointed protectors of all things safe and status quo have now determined the need to go after any writings that school-age kids might actually find engaging, unnerving and eye-opening.

There are a lot of dimensions to this: a strange combustible combination of White supremacy, anti-Semitism, historical denialism and hatred of the government, all creating a kind of politics that breeds hate, intolerance and violence. We saw it in the aftermath of the Civil War, when Reconstruction in the South gave way to racist dogma, lynchings and war on a nascent Black middle class. The later promise of Supreme Court decisions outlawing “separate but (un)equal” and the Civil Rights Movement also gave way to police repression, white “backlash” and the overtly racist “Southern Strategy” of the Nixon Administration and the War on Drugs by Reagan & Co.

Hope that the election of Barack Obama might make a substantive difference was soon undercut. After the Supreme Court gutted enforcement of civil rights and voting rights protections (Shelby County vs. Holder, 2013), attacks on people of color as a matter of public blood sport became commonplace. When Black Lives Matter arose to counter such mistreatment, white nationalism reasserted itself, whether wearing suit and tie and occupying Republican seats in legislatures or armed to the teeth and waving Confederate flags and swastikas as they threatened to overwhelm legislative chambers via a fascist putsch.

Without that as background, it is impossible to understand this latest incarnation of the culture wars that manifests itself in book banning and censorship. But this is no civil war between equally opposed forces, as if there were some equivalence between those in favor of squelching ideas and those who favor critical inquiry.

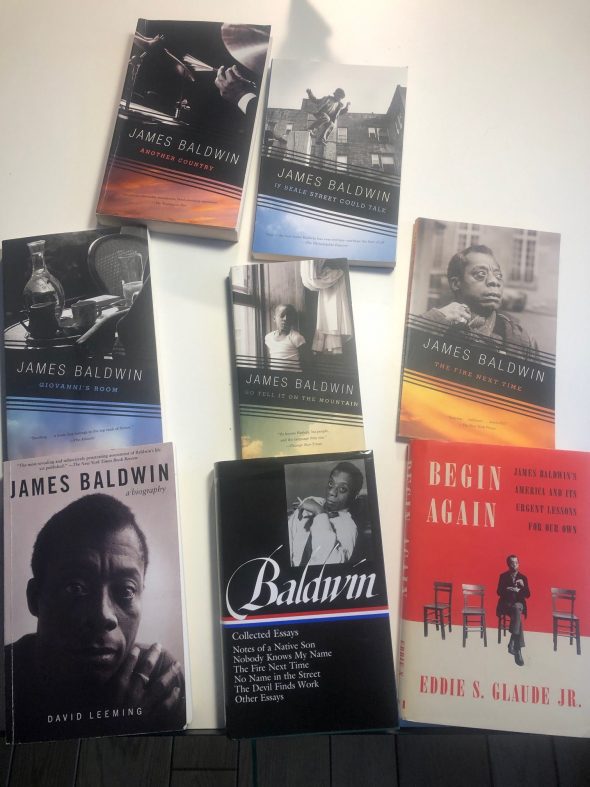

For the past year, a group of us in the Hartford, Connecticut area have been immersed in the writings of James Baldwin. We are all current or former academics, diverse in terms of gender, race, age, religion and nation of origin. What we really share is a love of books and of confronting complex ideas as we grapple with the underlying and very much unresolved issue of race in the United States and the world. For a year, now, every other week for an hour and a quarter, we’ve been plowing through Baldwin’s life and writings for lessons about how to think about race.

Baldwin (1924-1987) has been our guide, and it is a very stormy journey he takes us on. The tale moves uneasily from his upbringing in Harlem through his self-exile in Paris and Istanbul to his journeys through the American South at the outset of the Civil Rights Movement and to the subsequent tragedies of church bombings, violence against civil rights workers, police crackdowns, FBI harassment and assassinations – Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy, among them.

It’s a complicated, unresolved journey, one made even messier than the politics because of Baldwin’s personal struggles with his health, family and search for meaningful love. He was a relentless essayist and novelist, highly regarded in intellectual circles while widely read by the public. He was scathing in his assessment of how powerful a grip racism has had on the country. His central enduring insight about the corrosive effects of white supremacy was how it not only destroys the humanity of those who are its outward victims, but also how it eats up the soul of the racist, as well.

We live in ominous times. There is no telling for sure where the current venting of white supremacy and reaction is going to lead. There’s a good chance it will end in the demise of our democracy. The only way we as a country can make sure it does not is to confront head-on the ugliness and violence and rage that have lain at the core of the American dream. That, in a nutshell, is the sense you get from reading Baldwin. It’s the kind of unsettling lesson that a great writer evokes.

Those who would put an end to such a way of learning harbor a two-fold danger for the republic. On the overt level, they are hiding from some uncomfortable truths. More insidiously, they are telling us that learning itself is dangerous and that it is better to wallow in ignorance.

No school kid ever died from a reading group. And yet those who claim themselves “pro-life” and appalled at “cancel culture” don’t stand up to the real threats to learning: from school shootings and from censorious parents and administrators who simply want to deny uncomfortable truths. The racism here is so obvious. Notice, there is never any regard for the sentiments of the students of color who have to endure this tirade of white propaganda.

If you want to save students from discomfort, let them engage in messy conversations as they confront difficult ideas. We should be encouraging more reading, not prohibiting it.

Brad: this excellent post deserves a longer, more elaborate analysis in the form of an article for the “New Yorker” or “The Atlantic.” Since you’ve been so immersed in Baldwin, and given this good start, such a piece should not take you too long to write. I’m especially drawn to your interest in Baldwin’s focus on the soul-destroying capacities of white supremacy. This dovetails, as you know, with Leszek Kolakowski’s argument about authoritarians’ need to immobilize and incapacitate the person’s moral sense.

Scott, by the way, since you earlier had asked me, the place to start with Baldwin is with his journalistic essays, decidedly not his novels. The best place is “Nobody Knows My name.”

Well said Brad – unfortunately the people that would most benefit from reading Baldwin and other so called controversial books are generally to myopic in their world views to even consider it……

Great blog, Brad. I’ve never read any James Baldwin. I’ve read Malcolm X, Richard Wright, Colson Whitehead and others, but not Baldwin. Can you recommend one to start?

Thanks for the note, Alice. The best place to start with Baldwin is not with his novels but with his essays. I’d start with “Nobody Knows My Name.” There is also a fine volume of his collected journalistic essays that includes “Nobody Knows My Name” and four other books: James Baldwin: Collected Essays (The Library of America, 1998).

‘