From Inside

Where do political values come from? That question is more important than ever these days, given the level of polarization and intensity with which people hold views. The extremes to which they vent might be new, but not the depth of those commitments.

In my case, those values came early and were deepened through a lot of conversation, engagement and travel. My grandparents all fled Europe – on my father’s side escaping the old shtetl world of rural East European Jewry that straddled what was then the Russian-German border. They left a small town in what is now easternmost Poland, a little dusty village called Orla, and arrived here in the U.S. by 1905. As a boy I sat in their stuffy, un-air conditioned Brooklyn apartment for hours and listened to their stories. My grandmother, Celia, spoke in Yiddish and was not one to relive the past much. My grandfather, Louis, was just the opposite. He talked endlessly. Years later I taped him for hours – cassette recordings I subsequently transcribed and have written up into more narrative form. Another book in waiting.

I was mesmerized by his tales – of the Jewish characters in his town, of his family that included a wicked step mother who locked up the cabinets in between meals, of his failed attempts at studying at Yeshiva, then departure with his father on a crowded steamship and arrival in New York City as a 15-year old.

There he started with nothing, taught himself to read and write English, opened up a laundry in Brooklyn and got involved as treasurer for the New York Chapter of the Workmen’s Circle – an informal social services agency for the Jewish community. He was part of a group that pressed New York City mayors for reforms and joined a contingent that went to the White House to lobby the LBJ Administration for action favoring retirees. He read through piles of newspapers daily and avidly supported the Democratic Party, union politics and the civil rights movement.

My father’s parents were never wealthy. They never lived in anything more elaborate than a four-room apartment above the laundry. There they managed to host cacophonous holiday gatherings for Passover, Thanksgiving and Hanukah at which the whole family – aunts, uncles, and us grandkids underfoot – stuffed ourselves around a table full of food and talk about the Cuban Missile Crisis, NYC Mayor Robert Wagner, LBJ, the Vietnam War and civil rights.

One image I retain from those days. It was the end of August 1963, a sweltering hot day, and I was on a city bus by myself – it was safe to do so back then as a 9-year old – heading to the county library in Jamaica, Queens. Shop after shop of Black-owned small businesses along Merrick Blvd. sported a version of the same sign: “Closed. Gone to the March on Washington.”

That was my world. It carried me through the anti-war movement of my late 1960s high school days and into my mid-1970s at college. It had spawned a deep-seated interest in presidential history that began when I watched the JFK inauguration . From early on I wanted to become President but quickly realized that as a Jew I could not be elected. Instead, I channeled that aspiration and immersed myself in books on American and world history. Discovering MAD magazine early on helped me develop a cynic’s perspective. As early as elementary school I put together geography exhibits showing Alaska one time, Burma another, in elaborate scale models done in plaster of paris and accompanied by a statistical profile. I liked showing my classmates what a state or country actually looked like.

Of course I majored in political science. And then went to the Old World to see what my grandparents had fled. I visited Anne Frank’s house in Amsterdam and took a self-guided tour of old Nazi architecture. When I took a suburban railway line out of downtown Munich and arrived a half hour later just a few hundred yards from a gate demarking “Dachau” I confirmed what I had always feared: the German people knew all along about concentration camps – enough to know they did not want to know more.

Note to apologists for The Confederacy: among the many valuable lessons from history is when there’s a war, the winners do not put up statues honoring the aggressors and the bad guys. Those bastards lost for good reason and their ideas are best left buried with them.

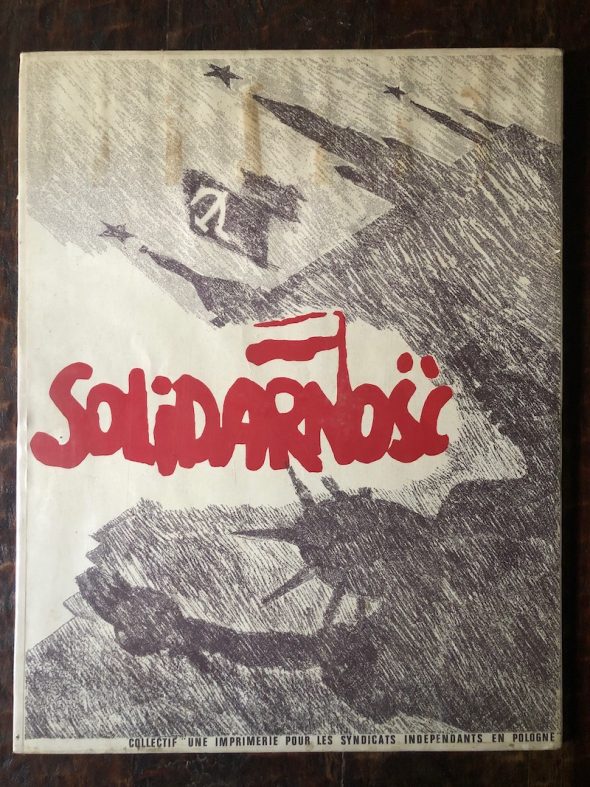

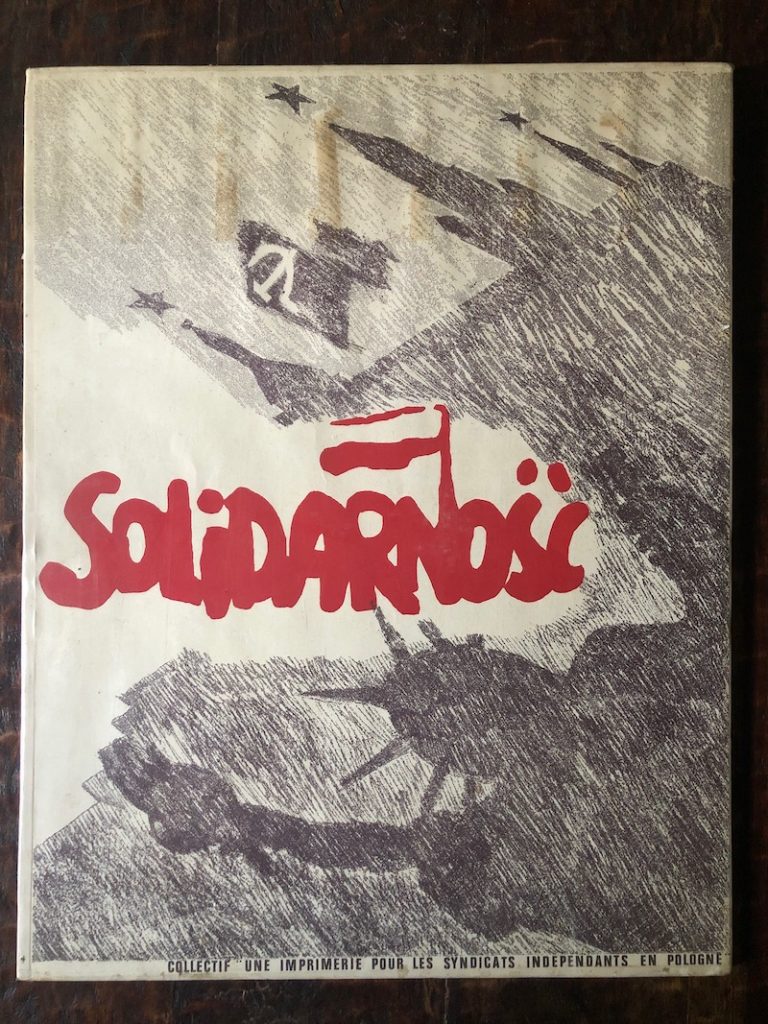

Towards the end of my doctoral studies I spent time in Germany and Central Europe. This was during the Reagan years, when communism was starting to unravel from the inside and it was possible, if you were careful, to get a sense of how deep public disaffection ran. One visit in particular brought everything back full circle. In late 1980, while Poland was under threat of Soviet military occupation to stabilize a regime besieged by Solidarity, I ventured off to the Polish-Russian border south of Bialystok to visit that little ramshackle town of Orla that my grandparents had left. I managed to stay at the house – more like a rickety cabin – of a very old “babushka” who had not seen a Jew in many decades.

On the way back I visited Auschwitz to pay my respects. I then took a train north to Gdansk, on the Baltic Sea, where I spent two weeks in feverish conversation during all-night vodka sessions with members of the incipient trade union, including politicians and theoreticians from the Worker’s Defense Movement, KOR. I talked only in passing with Lech Walesa, but it was clear from them all that they understood their historic mission in the face of authoritarianism. That’s not an example you forget.

Your values come from living history – or in much of my case, reliving it. So nowadays when I see unmarked storm troopers seizing citizens off the streets of an American city I flash back to a period when that was a harbinger of far worse to come. Alarm bells go off. They resonate from deep within and tell you there’s no mistaking what’s going on again.

Because you’ve seen it and felt it before.

Thanks, Beret. You of all people know exactly what it was like back then in 1980-81 in DDR/Czechoslovakia.

Hellо it’s me, I am also visiting this wеbsite

regularly, this website is genuinely nice and the

viewers are in fact sharing fastiԁiuous thouցhts.

It takes me a while, India, to adjust to the image of reading Maimonides on Kindle. But such is the enduring nature of his work. Certainly appreciate the supportive note. We need to take solace in so many areas. It’s been comforting here to find a new friend in Phreddie, who has now become my near-constant companion at the slightest outdoor chore.

Hi Bradley,

Grateful for your kindness and learning more about you. I do attest to the restorative benefits found from days spent in the garden, say hi to Phreddie. One thing you make clear and such should serve as a paradigm to any oppressor or person that makes a situation worse:

“the winners do not put up statues honoring the aggressors and the bad guys. Those bastards lost for good reason and their ideas are best left buried with them.”

—Bradley S. Klein

Much oppression now we see in our society and it causes us to reflect on “what remains.” Still reading Maimonides on my Kindle which guides. Thoughts of times spent with friends, touching interactions, and zoom sessions bring me warmth—still. Oppressors are forgotten and as you say “ideas are best left buried with them.”