Novel Approaches

We’re being tested daily like never before. Not for the right thing, however. We’re being tested emotionally, physically, in our tolerance levels of extreme social conditions. We should be undergoing tests for the virus more frequently. Because we are not, we are being put through the wringer and confronting a quality of daily life that is the stuff of a novelist’s imagination.

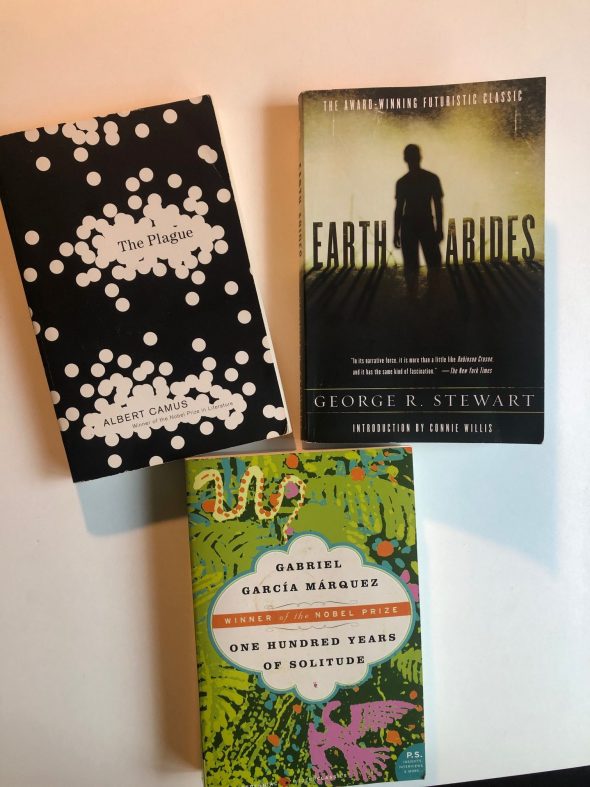

Like lots of people I have been trying to make the best use of my time. I’m also spending a lot less time watching TV and especially avoiding the day-to-day news barrage. Not that I am unaware of it. On the contrary, it plays like a recurring earache in the back ground no matter where I go or what I do. But I try to feed my brain on healthier, more substantive fare. Lately that’s included a number of novels that might best be described as negative utopias. In fact, they cross genres and literary boundaries, from “magical realism” to “existential” to “post-apocalyptic.”

For a lot of people, works portraying “the worst of all possible worlds” are a depressing turnoff that’s best avoided. No argument there. It’s a matter of disposition. I’ve always been more comfortable confronting what I take to be brutal truth than ducking it or preferring to be entertained instead. Of course it’s also a matter of degrees. A steady diet of anything is probably unhealthy. But having worked my way through studies of authoritarianism, the Holocaust and nuclear war, it hasn’t been much of a misstep to contemplate works that confront the possibility of widespread epidemic. And no, I am not a chronic depressive: as a partial antidote to all that doom and gloom I indulge in lots of playful reading and following of sports.

There is, however, something to be gained by losing oneself in the imagination of a creative mind that that can conjure up fables and epic tales about human fate and civilization. That’s the virtue of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” (1967). It’s about the bewildering fate of an isolated town in Colombia that endures seven generations of war, political misrule, family infighting and incest, and technological backsliding. Cause and effect are impossible to discern. Imagination, magic and fantasy run riot and have material substance of their own. It’s a book that completely unhinges conventional narrative flow and sequence.

Albert Camus’ “The Plague” (1947) is also focused on a singular community, but in this case, the decay is entirely self-contained in the form of an epidemic. The setting is the French Algerian port city of Oran, along the Mediterranean Sea. A year-long plague devastates the city, and despite the efforts to close the town from outsiders there is no containing the steady flow of bodies to the morgue. Along the way we see how various characters respond to the public health crisis. Some, like the main character, Dr. Bernard Rieux, dutifully attend to the afflicted. Others seek escape, to profit, or, in the case of a popular priest, to justify the disease as a form of punishment for widespread sin.

As an account of how a city gets transformed virtually overnight into the equivalent of a large clinic, “The Plague” is a very powerful tale. I found it less convincing as Camus’ extended metaphoric way of discussing resistance to the fascism that descended upon much of Central Europe in the 1930s and that ultimately occupied France under the Vichy Regime during World War Two.

Both of these books, by Garcia Marquez and Camus, drew widespread acclaim immediately upon publication and led to their authors winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. By contrast, George R. Stewart’s “Earth Abides” (1949) has enjoyed little more than cult status for its post-apocalyptic vision of American life. Yet given what we are going through and how things might play out if we don’t get a grip on the Covid-19 virus, this might prove to be the most revealing vision of all.

There are, after all, some circles in American epidemiology – and in popular culture as well – that are not beyond considering the possibility of an “extinction event.” Not that the coronavirus meets that threshold. But the whole point of public health is to guard against massive outbreaks that could have consequences so devastating that the loss thus far of 165,000 American lives or 725,000 worldwide would seem modest by comparison.

Stewart’s book does not shy away from contemplating a virtual extinction of the human race from some unnamed, very fast-acting epidemic that leaves only a few thousand survivors scattered across the landscape. Among those who for unexplored reasons manage to live through “the Great Disaster” is Isherwood “Ish” Williams. Note: his name is obviously a nod to the real-world “Ishi,” who in 1916 was the last known member of a California Native American people.

But now it’s post-World War Two America, and “Ish” sets out to see what remains of the country, and more importantly, of the people, plant life, animals and landscape following this near extinction event. The book follows over four decades of succession, during which “Ish” meets and then couples with a woman and joins a few others gradually to form a tightly-knit tribe in the East Bay of Northern California.

There is no federal government, no authority or police, no ability to maintain an infrastructure of highways, utilities, food supplies and medicine. The folks who remain get by mainly by scavenging remaining supplies, whether by raiding grocery stores and pharmacies, relying upon an existing electric grid, or tapping the remaining supplies from reservoirs and fuel depots. Eventually, those give out and the tribe is forced to make do on the basis of very limited skills and crafts.

Those lost skills include a sense of the wider achievements of civilization. Two generations after The Great Disaster, those born into the new world know nothing of The Old Times but its remnants. “Ish” is clearly worried and tries to cultivate an appreciation for skills than can help the nascent new society not just survive but thrive.

Books are crucial in this effort. Also, a certain temperament open to exploration and new concepts that are not immediately within one’s field of view. This where he really worries about the world around him as he ages. There’s a particularly moving segment where “Ish” revisits the vast university library on the campus (presumably UCal) where he had studied geography as a graduate student. As he wanders around the extensive, dust-laden shelves of the decrepit building, “Ish” tenderly leafs through volumes that have gone unread since the epidemic. He comments on their fate in a lament that resonates widely today: “Books themselves . . . were nothing – without a mind to use them.”